- They were kept sequestered behind fences, curtains, and screens, with their only face-to-face contact being the women they worked with, certain family members, and their lovers/spouses. (Although, they were freely allowed to have lovers, provided they were of equal social standing, so that's a plus.)

- Women had absolutely no privacy amongst their peers; ladies-in-waiting all slept in the same hall, with the only delineation between bedrolls being 3ft.-tall standing screens. (cue the "not so hilarious" antics of having your secret lover stumble into the wrong cubicle under the darkness of night)

- The only time women were allowed to leave their confines were on scheduled field trips to observe a seasonal or cultural festival, go on a religious pilgrimage, prepare for a religious ritual, or take a leave of absence to visit their family. Luckily, if one was creative, one could make an excuse for just about any field trip (So, I hear the flowers down by the hot springs are really pretty this year. We're totally going to watch them bloom, and not, you know, to visit the hot springs. We swear.)

- Also, the Japanese at the time believed in Onmyōdō, a mixture of science and Chinese mysticism, in addition to practicing Buddhism, so their calendar was a highly complex tapestry of festivals and holy days of all different (sometimes conflicting) flavours.

Unfortunately, the role of women in these events generally boiled down to "observe through the partially-obstructed window of their carriage," "sit in public with their faces hidden behind a screen," or "slave for hours making clothing and decorations for other people" (although we have documented accounts of women cajoling men into decorating the outside of their carriage in flowers for them, during a particularly relaxed spring outing).

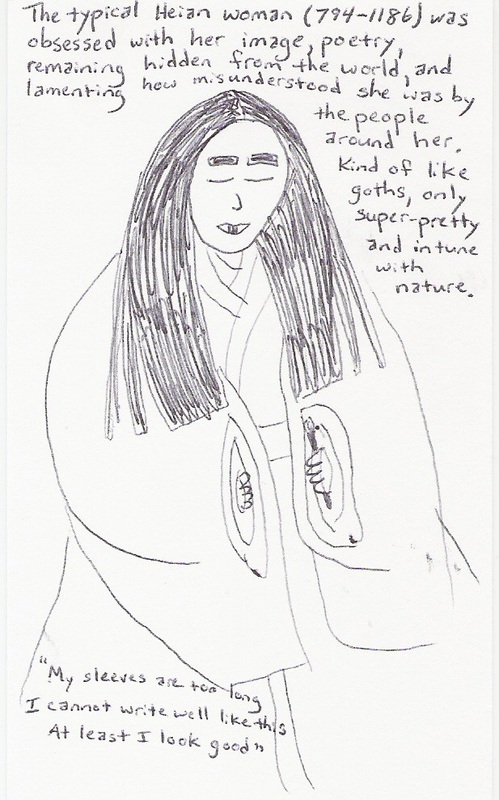

- Both courtiers and ladies-in-waiting did not usually have to fear for their lives or safety, but they were treated like performing pets (both by the nobility, and to a certain extent by each other), and every detail of their life was judged and scrutinized - they could lose court favour (which would not only endanger their position, but would also bring shame to their family's reputation) for such offenses as mismatching their clothing (easy to do with more than 12 layers of traditional "juni-hitoe" robes), not being able to generate witty puns or haiku on command, using the wrong type of paper for a letter, missing literary references in conversation, or (for women) showing their face to a man in public. (Think court of Versailles + constant SAT tests.)

- As preparation for their duties, court women were all taught to read and write (yay!), but they were also required to memorize thousands of pages of poetry, literature, and history in order to keep up with, and produce, interesting conversation and writings (boo!) However, some women truly excelled in this environment. Our only candid first-hand accounts of this era were penned by a woman, Kiyohara Nagiko (better known by her title of Sei Shōnagon), and one of the most famous epics in literary history, Genji Monogatari, was written by her rival and fellow lady-in-waiting Murasaki Shikibu. These documents are the main sources we have today in understanding the lives of women then, and allow us to see the full range of their joys and sorrows.

[Source: general study of the era, including two different close-read translations of Sei Shōnagon's writings. The only thing I double-checked before writing this post was how to spell the names.]

(Also, goths can be super-pretty and in tune with nature, too.)

(Additionally, I really like parentheses.)

RSS Feed

RSS Feed